By Sarah Kerrigan

Student-Attorney, International Human Rights Clinic

George Washington University Law School, Washington D.C., USA

Imagine taking a trip with your family. You finally get to the hotel and begin to check-in, and the person at the front desk asks for everyone’s ID. Continuing with the standard process, they type the information into the computer, make sure the rooms are ready, and prepare the room keys. Soon after, much to your surprise, a member of your family is arrested in relation to a Tweet they posted critical of the government, because the personal data associated with their ID was automatically matched to the police crime database during check-in. This would be inconceivable in a democracy that purports to respect its citizens’ civil and human rights. But with Hotel Eye in Pakistan, the possibility cannot be ruled out. And while such a system may help protect citizens from, say, murderers, it can also be used to track down a member of your family who posts comments on social media critical of the government.

In fact, Pakistan has one of the world’s largest biometric databases of its citizens. The National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA), for the purpose of identity card holding, collects and stores a person’s fingerprints, photograph, signature, and even iris scans. Avoiding this is near impossible, as the identity card is required to vote, open a bank account, get a passport or driver’s license, and get a cell phone. This system is shared with law enforcement agencies, making Hotel Eye possible. And Hotel Eye isn’t the only method of real-time monitoring. Travel Eye requires the IDs to be scanned before getting on any train or bus, and the Safe City Project monitors all people at entry and exit points of buildings and vehicles on roads. These systems can help increase security when administered responsibly, of course, but they can also be misused to undermine civil liberties. How much government surveillance is too much? And when does the risk of overreach and government abuse outweigh the purported benefits of such surveillance systems?

These questions are more relevant now than ever. The Pakistani Government has introduced troubling new Rules that threaten to expand its already expansive surveillance abilities even further into the digital realm. In particular, Pakistan’s Citizens Protection (Against Online Harm) Rules, 2020 (the Rules) establish a data localization provision, which would require internet companies to store or process user information on servers physically located in the country’s territory. Specifically, the Rules require social media companies to “establish one or more database servers in Pakistan” within one year of the rules entering into force. The Rules state that the purpose is for “citizen data privacy.”

However, given the already extensive government practice of surveilling citizens described in the opening paragraphs, it is doubtful that Pakistan’s data localization rules are intended only, if at all, for the purpose of protecting privacy. That surveillance becomes even more problematic when viewed in light of Pakistan’s routine abuse of the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 (PECA) to pursue people judicially for social media posts deemed undesirable, or to harass journalists that criticize the government or military. So, it seems likely that the Rules’ efforts to compel data localization by companies can be better explained by the Pakistani authorities’ desire to assert territorial jurisdiction — and thus control — over citizens’ data captured by internet companies, primarily those operating social media platforms, which would make it easier for the government to persecute critics for their online activities.

Why do countries want data stored within their borders anyway? Usually, it is because governments are able to access and control citizens’ data on social media more easily when the data is stored in their territory and local laws enable this access. Today, we live in a world in which the internet is accessible globally. This is possible due to many organizations, especially companies and sometimes governments, sharing the electronic data that underlies everything on the internet across their borders. While this data sharing is essential for the free flow of information, it raises questions of who controls the data, and thus has access to its content and holds its value.

There is a heated debate over how countries can and should have access to digital data from online platforms, and when and under what circumstances. One governmental response has been data localization laws. These require companies to build and house servers in the territory of that country, to open a local office, and to register with its authorities. Data localization laws give countries direct control over the data when it is stored on their territory, allowing them to access it as they please. This occurs particularly when there are few or no safeguards to protect user data in local legislation. One example in Pakistan is the statutory obligation under PECA establishing a need for warrants to pursue such data, which is not enforced. Ostensibly, the government claims to want to protect their citizens’ data; however, more often than not, it wants to make the data more readily available to law enforcement to facilitate surveillance.

Although no international standards govern data localization itself, international human rights law does impose obligations and limits on governments with respect to privacy and other human rights affected by such laws, such as freedom of expression. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a human rights treaty which Pakistan has ratified, provides for a right to privacy. This includes a duty to ensure that data is never used for purposes incompatible with the ICCPR. Surveillance is allowed in limited circumstances, but these circumstances must be written in law, necessary and proportionate to the aim that is pursued. Even assuming a legitimate purpose, Pakistan’s likely use of data localization powers to allow for even more real-time, constant monitoring is unquestionably not limited to certain critical circumstances, and would be a threat to the right to privacy.

Whether privacy rights are respected also has a direct impact on freedom of opinion and expression. Facilitating the state’s access to user data would allow the Pakistan government to continue and expand its practice of censoring its citizens’ social media posts under PECA. This would further undermine freedom of expression as guaranteed by international human rights law. Although some restrictions on free speech are allowed, it is inconsistent with international human rights norms to prohibit expression solely on the basis that it is critical of the government or state institutions Despite these international legal standards, countries have enacted data localization laws that make it easier for them to access user data, surveil citizens, and control “free” speech on social media.

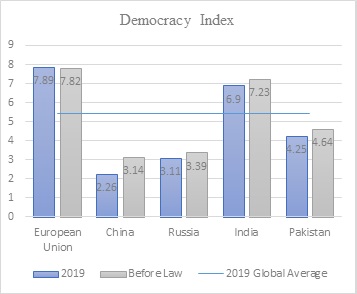

Experience shows that most efforts at localization of data in other countries have led to greater authoritarianism and less democracy. In the places with the strictest data localization laws, like China and Russia, neither a paradigm of democracy to begin with, there seem to be declines in citizens’ privacy, as measured by Freedom on the Net index, and democracy, as measured by the Economist’s Democracy Index.

In China, the 2016 Cybersecurity Law took effect in 2017, requiring “critical information infrastructure” operators, particularly publishers of online content, operating in the country to store data on servers located in China. This gives China the ability to demand the data is turned over at any time it deems there is a national security reason. China has few privacy protections, and its control over the communications is seen by an instance of an individual being jailed for criticizing the government on a “private” social media platform, WeChat. Since the data localization law took effect, China’s levels of privacy have decreased. China’s Freedom on the Net score decreased from 12 in 2016 to 10 in 2019. Levels of democracy in China have also decreased during this time. The Democracy Index decreased from 3.14 to its current index of 2.26. China’s decline in democracy between 2018 and 2019 represented the greatest decline in the world and was explained in part by digital surveillance of the population.

In Russia, Federal Law No. 252-FZ requires companies collecting personal information about Russian citizens to “record, systematize, accumulate, store, clarify (update or modify), and retrieve” the information using servers physically located within Russia. Like in China, the Russian government also uses this law for intensive state surveillance of internet activities. This allows for censorship of anything deemed to be extremist, such as when a young father’s home was raided by a SWAT team and he was arrested and imprisoned for resharing a meme of a toothpaste tube critical of Russia on social media. Since Russia’s data localization law took effect in 2015, the levels of privacy in the country have decreased. The Freedom on the Net score in 2014 was 40, but is now 31. Unsurprisingly, this abuse of privacy caused its measurement of democracy to decrease (Russia’s Democracy Index fell from 3.39 to 3.11).

These examples make clear the threat that data localization laws pose by facilitating increased surveillance and social control by authoritarian regimes. Overly broad surveillance by governments undermines privacy rights and civil liberties, impacting governments’ international legitimacy, especially if they purport to be a democracy as Pakistan does. This is not to say that data localization laws can never work. In Australia, the My Health Records Act has successfully protected its citizens’ privacy. The Act is restricted to one sector, requiring only electronic health record data to be stored in Australia. Australia’s Freedom on the Net score is 77 and the Democracy Index is 9.09, representing high levels of privacy and democracy. Nevertheless, countries with draft data localization laws, like India and Pakistan, may have trouble avoiding the same fate as China and Russia if they continue with their plans.

In India, a draft Personal Data Protection Bill would require personal data to be stored on a server or data center located in India. There is a legitimate worry that this would give the government an unchecked power to surveil its citizens because there are weak safeguards to prevent abuses of state surveillance in India. Furthermore, even since the first proposal of the draft bill in 2018, the privacy of citizens has decreased (the Freedom of the Net score in 2017 score of 59 fell to 55 in 2019) as well as its levels of democracy (the Democracy Index falling from 7.23 to 6.90 during the same period). To remedy these privacy concerns, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy has called on India to put a check on the surveillance powers, such as procedural safeguards and governmental accountability, in order to comply with the right to privacy.

What does this all mean for Pakistan? If Pakistan truly wanted to protect citizen data, it would be enacting robust privacy protections, not data localization laws. For example, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) restricts the transfer of data from the EU to countries in which there is at least the same or better protection for users’ data and therefore their privacy. The GDPR is designed to give greater privacy protections to EU citizens. The GDPR complies with international law by limiting companies’ ability to collect and use people’s data safeguards the right to privacy. It should be no surprise that of the EU countries studied by Freedom House, all of them rank very favorably on the Freedom of the Net scores. Additionally, since the GDPR was in effect in 2018, all the countries in the EU on average tended to become more democratic.

Recently, on April 9, 2020, the Pakistan Government introduced its own draft Personal Data Protection Bill (the Bill) that broadly mirrors the GDPR in that it requires users’ consent to collect data, informing individuals of the collection of their personal data, and allowing users to request access to their personal data. It also restricts the transfer of data from Pakistan to countries in which there is at least the same or better protection for users’ data.

This effort is commendable because it could improve privacy protections if international human rights standards are adhered to. However, the Bill may not protect personal data from state surveillance because broad exceptions — allowing collection and storage of personal data “for legitimate interests,” which is undefined by the Bill, and giving the government the ability to exempt any provision from applying to itself — could easily be abused and undermine the stated purpose of the Bill. Furthermore, the Bill would codify the data localization provision in the Rules into law because it requires “critical personal data” to be processed only on servers in Pakistan. What is to be considered “critical personal data” will be defined after the Bill is passed by the authority established in the proposed law, which is to be wholly appointed by the Federal Government. Given the history of actions of similar authorities under PECA, it is possible that the surveillance concerns under the Rules would merely be made law if the Bill is passed as it currently stands.

Do you feel like you’re being constantly watched or surveilled? This feeling should not go away until Pakistan removes the data localization provisions from the Rules and the Bill. Data localization will allow for easier state access to data and thus enhanced surveillance capabilities beyond that currently carried out in hotels and public streets or buildings by bringing it into your own home through social media. If Pakistan does not remove the provisions, it will become all the more difficult to defend its democratic credentials (the country’s Democracy Index has fallen since PECA was enacted in 2016, and it can expect its Freedom on the Net privacy scores to continue to fall along with its legitimacy).

Thus, Pakistan would benefit from first enacting robust privacy protections that limit opportunity for state surveillance (it doesn’t help that the draft Personal Data Protection Bill 2020 could exempt the government from any such restrictions). For example, a court order should be required before law enforcement is able to obtain personal data. In addition, the circumstances and the nature of the threat in which requests for warrants can be made should be clearly outlined in PECA and Rules under it, while noting that the circumstances provided for cannot restrict freedom of expression. In the event that Pakistan does collect the personal data of a person, it should notify them of the content of the data and why it was collected. Until then, citizens and social media companies should push back against Pakistan’s efforts to compel control of their data in order to defy their users’ rights.

[*] Freedom House, a non-governmental and non-partisan organization, publishes an annual Freedom on the Net report measuring the level of internet and digital media freedom in 65 countries. Countries are rated on a scale of 100 to 0, with 100 being the most free and 0 being the least free. The considerations are any obstacles to Internet access, limits on content, and violations of user rights. Note that in 2015 and prior reports a rating of 100 represented the least free and 0 represented the most free; thus, here the ratings prior to 2015 have been inverted in order to be compared to the current rating methodology described above.

[†] The Democracy Index is compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit. The index provides a measure of democracy of every country in the world on a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 being the least democratic and 10 being the most democratic. The index is based on the electoral process, civil liberties, the functioning of government, political participation, and political culture.